ROPing on RISC-V - hack-a-sat23

2023, May 5

This post is about creating a pwn environment for RISC-V, exploiting RISC-V binaries, and doing ROP chains on RISC-V. We will use as our target binary to pwn, the drop-baby binary from hack-a-sat CTF 2023.

nikos@ctf-box:~$ file drop-baby

drop-baby: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, UCB RISC-V, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, for GNU/Linux 5.4.0, with debug_info, not stripped

Setting up an environment

Before we can begin diving into exploitation, we need to set up our RISC-V pwning environment.

We will use QEMU to emulate the binary, binfmt for seamless interaction with the binary, gdb-multiarch to debug it, pwntools to programmatically interact with it and write our exploit script, binutils-riscv64-linux-gnu for generating shellcode (assembler), and ROPgadget to find ROP gadgets in RISC-V binaries. Since this is cutting edge stuff, it is always recommended to run on the latest version.

Vanilla environment

Let’s start with the vanilla environment, so QEMU, binfmt, binutils, and GDB:

sudo apt update

sudo apt-get install -y \

binutils-riscv64-linux-gnu binutils-doc \

binfmt-support \

qemu qemu-utils \

qemu-user qemu-user-static \

qemu-system qemu-system-misc \

gdb-multiarch

sudo apt-get install gcc-riscv64-linux-gnu # optional. For using gcc to produce risc-v 64-bit binaries.

pip install --upgrade pwntools ROPgadget

If everything has been done installed correctly, you should now have entries registered in binfmt about RISC-V:

nikos@ctf-box:~$ update-binfmts --display

qemu-riscv32 (enabled):

package = qemu-user-static

type = magic

offset = 0

magic = \x7f\x45\x4c\x46\x01\x01\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x02\x00\xf3\x00

mask = \xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\x00\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xfe\xff\xff\xff

interpreter = /usr/libexec/qemu-binfmt/riscv32-binfmt-P

detector =

qemu-riscv64 (enabled):

package = qemu-user-static

type = magic

offset = 0

magic = \x7f\x45\x4c\x46\x02\x01\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x02\x00\xf3\x00

mask = \xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\x00\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xfe\xff\xff\xff

interpreter = /usr/libexec/qemu-binfmt/riscv64-binfmt-P

detector =

And you should also be able to simply run the binary:

nikos@ctf-box:~$ file drop-baby

drop-baby: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, UCB RISC-V, RVC, double-float ABI, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, for GNU/Linux 5.4.0, with debug_info, not stripped

nikos@ctf-box:~$ ./drop-baby

No flag present

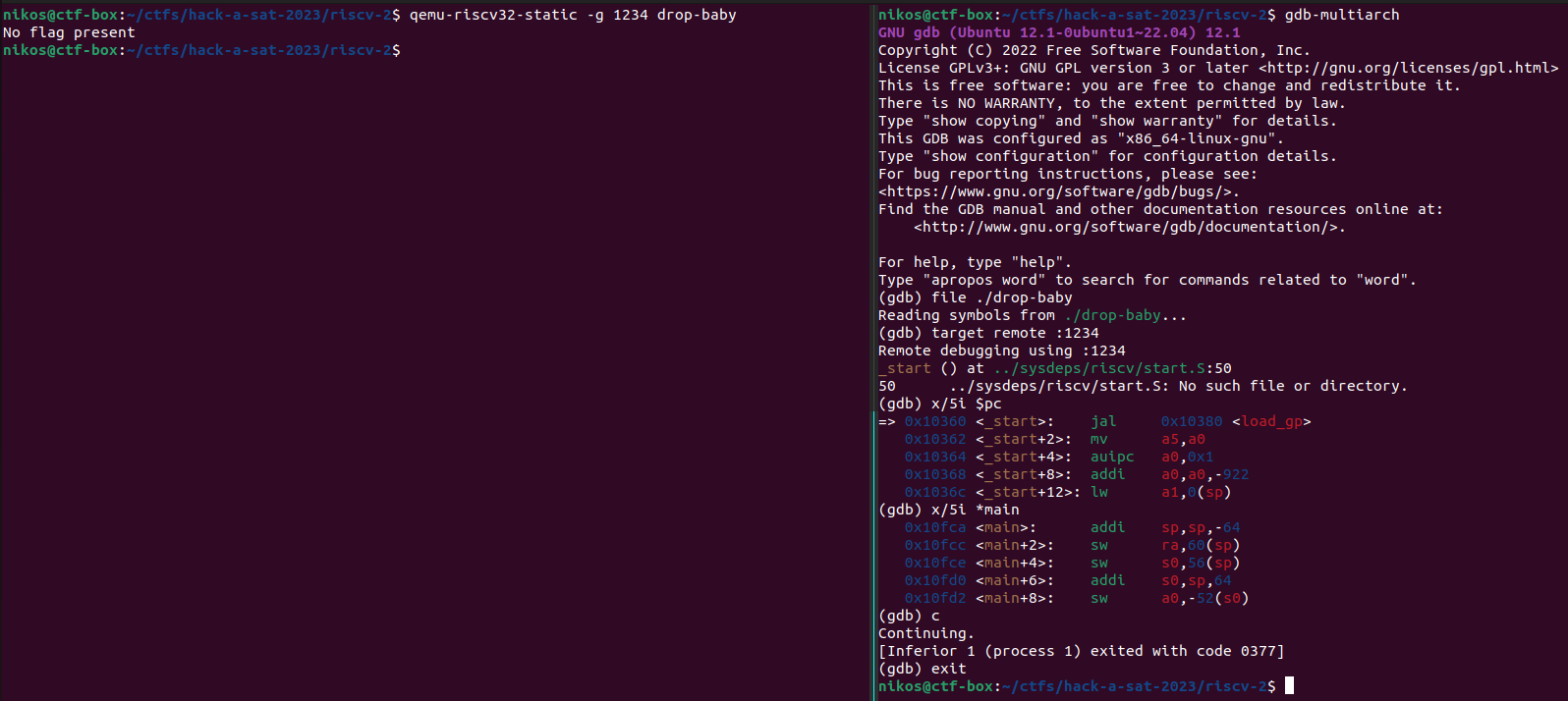

You should also be able to run the binary under gdb-multiarch:

Great!

pwntools environment

Now, let’s make sure that pwntools with gdb also works (by default, in version <4.9.0, they won’t). Let’s make a template pwntools and run it:

# minimal-template.py

# A minimal custom template for binary exploitation that uses pwntools.

# Run:

# python minimal-template.py [DEBUG] [GDB]

from pwn import *

# Set up pwntools for the correct architecture. See `context.binary/arch/bits/endianness` for more

context.binary = elfexe = ELF('./drop-baby')

print(context)

def start(argv=[], *a, **kw):

'''Start the exploit against the target.'''

if args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([elfexe.path] + argv, gdbscript, elfexe.path, *a, *kw)

else:

target = process([elfexe.path] + argv, *a, **kw)

return target

# Specify your gdb script here for debugging. gdb will be launched the GDB argument is given.

gdbscript = '''

# init-gef

# continue

'''.format(**locals())

arguments = []

io = start(arguments)

io.interactive()

io.close()

nikos@ctf-box:~$ python minimal-template.py

[*] '~/drop-baby'

Arch: riscv-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x10000)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 785, in arch

defaults = self.architectures[arch]

KeyError: 'em_riscv'

During handling of the above exception, another exception occurred:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "~/minimal-template.py", line 8, in <module>

context.binary = elfexe = ELF('./drop-baby')

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 176, in fset

self._tls[name] = validator(self, val)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 872, in binary

self.arch = binary.arch

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 176, in fset

self._tls[name] = validator(self, val)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 787, in arch

raise AttributeError('AttributeError: arch must be one of %r' % sorted(self.architectures))

AttributeError: AttributeError: arch must be one of ['aarch64', 'alpha', 'amd64', 'arm', 'avr', 'cris', 'i386', 'ia64', 'm68k', 'mips', 'mips64', 'msp430', 'none', 'powerpc', 'powerpc64', 'riscv', 's390', 'sparc', 'sparc64', 'thumb', 'vax']

Hmm interesting. It seems that the pwnlib library knows about 'riscv' architecture but not about 'em_riscv' (upstream issue here). Anyway, we know already that our system can run the binary so let’s add a small patch to the ~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/elf/elf.py file of the pwnlib library.

diff --git a/elf.py b/elf.py

index c6e6708..7f89bd8 100644

--- a/elf.py

+++ b/elf.py

@@ -481,7 +481,8 @@ class ELF(ELFFile):

'EM_PPC64': 'powerpc64',

'EM_SPARC32PLUS': 'sparc',

'EM_SPARCV9': 'sparc64',

- 'EM_IA_64': 'ia64'

+ 'EM_IA_64': 'ia64',

+ 'EM_RISCV': 'riscv'

}.get(self['e_machine'], self['e_machine'])

@property

Let’s try running it again now:

nikos@ctf-box:~$ python minimal-template.py

[*] '~/drop-baby'

Arch: riscv-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x10000)

ContextType(arch = 'riscv', binary = ELF('~/drop-baby'), bits = 32, endian = 'little', os = 'linux')

[+] Starting local process '~/drop-baby': pid 5541

[*] Switching to interactive mode

No flag present

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

$

[*] Process '~/drop-baby' stopped with exit code 255 (pid 5541)

[*] Got EOF while sending in interactive

Great! The binary works with pwntools. Let’s try pwntools+gdb now:

nikos@ctf-box:~$ python minimal-template.py GDB

[*] '~/drop-baby'

Arch: riscv-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x10000)

ContextType(arch = 'riscv', binary = ELF('~/drop-baby'), bits = 32, endian = 'little', os = 'linux')

[!] Neither 'qemu-riscv' nor 'qemu-riscv-static' are available

[ERROR] argv must be strings or bytes: [None, '--help']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "~/minimal-template.py", line 26, in <module>

io = start(arguments)

File "~/minimal-template.py", line 14, in start

return gdb.debug([elfexe.path] + argv, gdbscript, elfexe.path, *a, *kw)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 1578, in setter

return function(*a, **kw)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/gdb.py", line 539, in debug

sysroot = sysroot or qemu.ld_prefix(env=env)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/context/__init__.py", line 1578, in setter

return function(*a, **kw)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/qemu.py", line 162, in ld_prefix

with process([path, '--help'], env=env) as io:

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/process.py", line 258, in __init__

executable_val, argv_val, env_val = self._validate(cwd, executable, argv, env)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/process.py", line 518, in _validate

argv, env = normalize_argv_env(argv, env, self, 4)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/util/misc.py", line 204, in normalize_argv_env

log.error("argv must be strings or bytes: %r" % argv)

File "~/.pyenv/versions/3.10.5/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/log.py", line 439, in error

raise PwnlibException(message % args)

pwnlib.exception.PwnlibException: argv must be strings or bytes: [None, '--help']

From the error message Neither 'qemu-riscv' nor 'qemu-riscv-static' are available, it seems that pwntools searches for the qemu-riscv and qemu-riscv-static binaries. Let’s help it by making them point to qemu-riscv32 and qemu-riscv32-static correspondingly.

nikos@ctf-box:~$ ln -s /usr/bin/qemu-riscv32 qemu-riscv

nikos@ctf-box:~$ ln -s /usr/bin/qemu-riscv32-static qemu-riscv-static

nikos@ctf-box:~$ export PATH="$PATH:$(pwd)"

nikos@ctf-box:~$ ls

drop-baby minimal-template.py qemu-riscv qemu-riscv-static flag.txt

Let’s try again now:

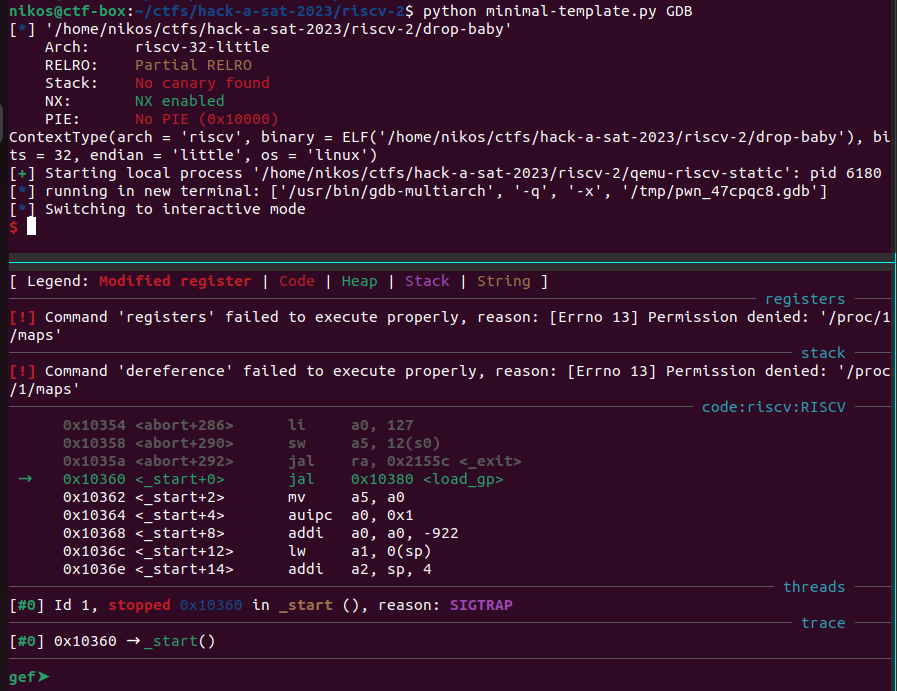

Perfect! Our RSIC-V pwning environment complete and we can start exploiting (finally)!

Source code

I won’t bore you with the reversing of the drop-baby binary. The goal is to get the flag and with that let’s jump straight into the buggy code:

int main() {

setvbuf(stdout,NULL,2,0);

char *flag = getenv("FLAG");

if (flag == NULL) {

puts("No flag present");

exit(-1);

}

//Crete flag.txt file.

//Read and write permissions for the owner of the file, and with no permissions for other users.

int flag_fd = open("flag.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY, 384);

if (flag_fd < 0) {

printf("Errno = %d trying to open flag.txt\n", errno);

exit(-1);

}

size_t sVar2 = write(flag_fd,flag,strlen(flag));

if (sVar2 != strlen(flag)) {

puts("Unable to write flag to file");

exit(-1);

}

close(flag_fd);

//!!! BUG: environment variable `FLAG` does not get wiped from memory. So, even if unsetenv

//is invoked, the value of the `FLAG` environment variable is still somewhere on the stack.

if (unsetenv("FLAG") == -1) {

puts("Unable to clear environment");

exit(-1);

}

//setup timeout signal based on `TIMEOUT` environment variable.

ulong timeout;

char *timeout_str = getenv("TIMEOUT");

if (timeout_str == NULL) {

timeout = 10;

} else {

timeout = strtoul(timeout_str,NULL,10);

if (timeout == 0) {

timeout = 10;

}

}

signal(0xe,alarm_handler); //puts("Time\'s up!"); exit(1);

alarm(timeout);

puts("\nBaby\'s Second RISC-V Stack Smash\n");

puts("No free pointers this time and pwning might be more difficult!");

puts("Exploit me!");

do {

if (syncronize() == -1) //`synchronize()` expects the following input: `\xde\xad\xbe\xef`

return -1;

int res = read_message();

} while (res != -1);

return -1;

}

int read_message(void) {

char control_chr;

ssize_t nread = read(0,&control_chr,1);

if (nread != 1)

return -1;

//`control_chr` can be one of the following:

// '\xa1', '\xa2', '\xb1', '\xb2'

//Only '\xb2' is relevant to us.

if (control_chr == '\xb2') {

return do_b2();

} else {

//...

}

return -1;

}

int do_b2() {

char acStack_78 [100];

if (read(0,acStack_78,sz) < 300) { //!!! BUG: BufferOverflow here.

return -1;

}

if (check_message_crc(acStack_78,300) == -1) //dumb CRC32 check. Last 4 bytes of input is the CRC32.

return -1;

return 0;

}

Here are the juicy parts from the code above:

- The binary reads two environment variables:

FLAGandTIMEOUT. TIMEOUTis (classically) used to prevent us from leaving open connections to the remote (nothing fancy). If not specified, it defaults to 10 seconds, so for our exploitation we will set it to something much higher (3600).FLAGenvironment variable contains the flag value and writes it to the fileflag.txt- The

unsetenv("FLAG")function simply unsets the environment variable. However, it does not erase the memory. It simply shifts the all the elements in thechar *environ[]array to the left by 1 (setenv.c#264). This means that the flag is still somewhere down the stack. syncronize()is a boring state machine. Required input is\xde\xad\xbe\xef.read_message()is where the program will read commands from us.- Command

b2reads300bytes into a buffer of100bytes. This is a buffer overflow.

- Command

Now that we have identified the location of the buffer overflow and how to reach it, it is time to come up with a strategy to pwn the binary.

Detour to RISC-V architecture and ABI

Before we attempt to exploit this buffer overflow, we need to understand our target architecture. More specifically:

- What is the function call convention?

- How are arguments passed to functions?

- How is the control flow transferred to a function

- How does a function return to its caller

- What is the syscall ABI?

- How are arguments passed to syscalls

- How does the stack behave?

- Which are caller/callee saved registers?

- Which are our registers?

- How does the assembly of RISC-V look like?

- How do we access memory?

Only if we know the answer to the above questions we can start thinking about exploiting and ROPing. Otherwise, we simply do not know how to control the program counter, how gadgets look like, and how to chain them together!

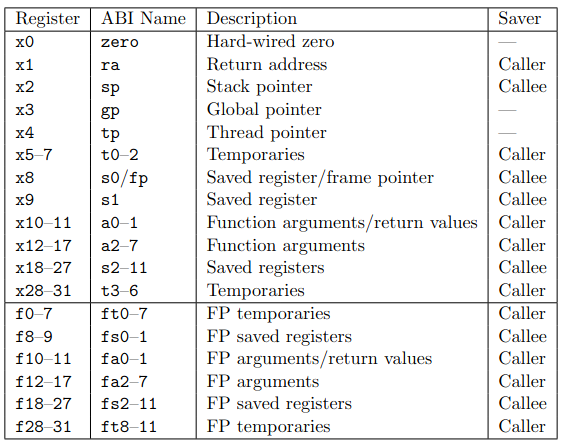

Registers

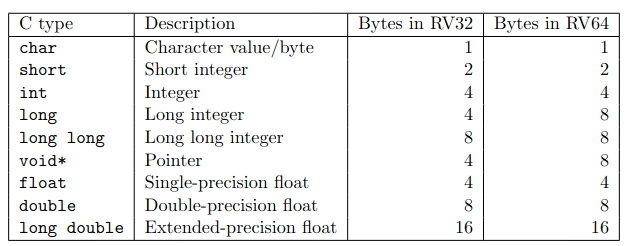

Datatypes

Function call convention

- Function call convention

- RISC-V has a little-endian memory system.

- In the standard RISC-V calling convention, the stack grows downward and the stack pointer is always kept 16-byte aligned.

- Function arguments are passed arguments in registers when possible. Up to eight integer registers,

a0-a7 - Return value is passed in registers

a0anda1.

Here is a simple example compiled using godbolt.org:

int myfunc(int arg) {

int i;

i=arg+0x20;

return i;

}

int main() {

myfunc(0x10);

return 0;

}

myfunc(int)-0x2:

nop

R_RISCV_ALIGN *ABS*+0x2

myfunc(int):

addi sp,sp,-16 # allocate stack

sw ra,12(sp) # store return address

sw s0,8(sp) # store frame pointer

addi s0,sp,16 # s0=sp

sw a0,-12(s0) # save arg0

# do the opration

lw a0,-12(s0)

addi a0,a0,0x20

sw a0,-16(s0)

# return

lw a0,-16(s0) # return value

lw ra,12(sp) # return address

lw s0,8(sp) # restore frame pointer

addi sp,sp,16 # deallocate stack

ret # pseudo-instruction: jalr x0, ra, 0

main:

addi sp,sp,-16

sw ra,12(sp)

sw s0,8(sp)

addi s0,sp,16

li a0,0

sw a0,-16(s0)

sw a0,-12(s0)

# prepare for function call to myfunc()

li a0,0x10 # setup arg1

# compute address of myfunc using relative addressing

# and then call it using jalr

auipc ra,0x0

R_RISCV_CALL_PLT myfunc(int)

R_RISCV_RELAX *ABS*

jalr ra # 3a <main+0x14>

lw a0,-16(s0)

lw ra,12(sp)

lw s0,8(sp)

addi sp,sp,16

ret

Other

- RISC-V Assembly Programmer’s Manual - Very good resource.

- RISC-V instruction set cheatsheet

- RISC-V instruction set reference

- Pseudo-instructions

- Assembler directives

- Relative/Absolute addressing, labels, GOT accessing

- Load & Store

Pwning

Now that we know our architecture, let’s identify the binary’s security properties and come up with an exploitation strategy:

nikos@ctf-box:~$ checksec --file=./drop-baby

[*] '~/drop-baby'

Arch: riscv-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x10000)

Great, no PIE!. Let’s search for useful gadgets using ROPgadget. Generally, we want to control:

a0,a1,a2,...when making function calls as these are the argument registersraas this is the return address where a function call should return when finished- Find

jrandjalrgadgets as these will compose our ROP chain.

Also, we notice in the disassembly that many instructions start with the c. prefix. These are compressed 16-bit instructions (RCV) instead of the regular 32-bit instructions and are referred in the “C” Standard Extension for Compressed Instructions in the RISC-V ISA:

The “C” extension can be added to any of the base ISAs (RV32,

RV64, RV128), and we use the generic term “RVC” to cover any of these. Typically, 50%–60% of the RISC-V instructions in a program can be replaced with RVC instructions, resulting in a 25%–30% code-size reduction.RVC uses a simple compression scheme that offers shorter 16-bit versions of common 32-bit RISC-V instructions

The C extension is compatible with all other standard instruction extensions. The C extension allows 16-bit instructions to be freely intermixed with 32-bit instructions, with the latter now able to start on any 16-bit boundary.

Here is a one liner to search for gadgets in our binary:

ROPgadget --binary drop-baby --align 4 \

| grep -E 'sw|swsp|lw|lwsp|mv|sub|add|xor|jr|jalr|ret|ecall' \

| grep -E '; (ret)|((c\.)?j(al)?r (x[0-9]{1,2}|zero|ra|sp|gp|tp|s[0-9]{1,2}|t[0-6]|fp|a[0-7]))$' \

| tee gadgets.log

- The first regex will filter gadgets that have only relevant opcodes to us.

- The second regex is about how the gadget should end. All of our gadgets will end with either

jrorjalrwith a register as argument.retis the same asjalr x0, ra, 0retis the same asjr ra- If we are doing function calls, we want our gadgets to not end with

j(al)?r ra. This is because the function call will use theraregister in theretinstruction to return to our next ROP gadget.

- We are interested in the

lwspgadgets as these gadgets can directly load values from the stack (which we control) into our registers ecallis uses for invoking syscalls, but we have libc statically linked so we don’t use it.- Since our binary supports the

c.prefix, we can also--align 2instead of4.

Here are some example good quality gadgets:

# Control a bunch or registers

0x0001a7e8:

c.lwsp ra, 0x2c(sp) ;

c.lwsp s0, 0x28(sp) ;

c.lwsp s1, 0x24(sp) ;

c.lwsp s2, 0x20(sp) ;

c.lwsp s3, 0x1c(sp) ;

c.lwsp s5, 0x14(sp) ;

c.lwsp s6, 0x10(sp) ;

c.lwsp s7, 0xc(sp) ;

c.lwsp s8, 8(sp) ;

c.mv a0, s4 ;

c.lwsp s4, 0x18(sp) ;

c.addi16sp sp, 0x30 ;

c.jr ra

# Control a0, a1, a2 function arguments

0x00026900:

c.lwsp a2, 0x10(sp) ;

c.lwsp a1, 0x18(sp) ;

c.lwsp a0, 0x14(sp) ;

c.mv a5, s8 ;

c.li a6, 0 ;

c.li a4, 0 ;

c.mv a3, s6 ;

c.jalr s0

# Gadget that does not use `ra` to jump.

# Instead, it controls `ra`, so we can return from a function call back

# to our ROP chain.

0x0001a410:

c.lwsp ra, 0x1c(sp) ;

c.addi16sp sp, 0x20 ;

c.jr a5

With the lwsp instructions we can load arbitrary values into registers and with the addi16sp we can increase the stack pointer. The jr and jalr use a register to jump, whcih we we can control with lwsp, and thus we can link gadgets togeather.

Now for the ROP chain payload we have two solutions:

- solution-cheesy.py - Abuses the fact that the flag is still somewhere in the stack. It finds the address of the flag in the stack and then does

puts(flag). - solution.py - More hardcore ROP solution. It performs the following function calls with a ROP chain:After each function call, we re-trigger the buffer overflow as the whole ROP chain does not fit into the 300 bytes that we can write.

fd=open("flag.txt", O_RDONLY); read(fd, buf, 0x100); write(1, buf, 0x100); //write to stdout

When we execute our ROP chain, we get the flag!